“Rudolf the Red-Nosed Reindeer / Had a very shiny nose”

The story of the Rudolph who was mocked by his fellow reindeer for his glowing red nose but came to be loved after leading Santa Claus’ sleigh on a foggy Christmas Eve first appears in a booklet written by the American Robert L. May in 1939. A Chicago-based retailer named Montgomery Ward used to send out promotional booklets for free every Christmas, and to save on the costs of buying them from external suppliers, asked May to write a booklet himself—so Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer was born.

In 1949, May’s brother-in-law Johnny Marks, who was already active as a songwriter, wrote a song based on the story of Rudolph, and this was sung by Gene Autry. “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” became a massive hit, selling 1.75 million copies just in its first Christmas season.

The idea of flying reindeer pulling Santa Claus’ sleigh first appeared in a poem in 1821, and in 1823, the poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas” gives the names of eight reindeer: Dasher, Dancer, Prancer, Vixen, Comet, Cupid, Dunder, and Blixem. Dunder, which comes from the Dutch word for ‘thunder’, is sometimes also given in the Modern Dutch form Donder or the German form Donner. Blixem, from the Dutch word for ‘lightning’ (bliksem in modern spelling) is also given as Blixen or the German form Blitzen.

So Rudolph joined the Santa Claus mythology more than a hundred years after the other reindeer. But it became the most famous of the all.

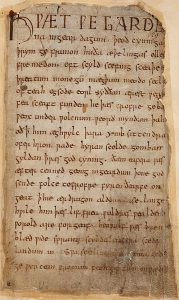

Now what if there is a poem in Anglo-Saxon (i.e. Old English, spoken from the 5th to the 11th century) about Rudolph? Let’s take a look first at the poem, whose first line (starting “Incipit”) is in Latin. The letters Ð/ð (eth) and Þ/þ (thorn) used in Old English represent the sounds written ‘th’ in Modern English, both the voiced dental fricative [ð] and its voiceless counterpart [θ], without a strict rule on which letter represents which of the pair.

Incipit gestis Rudolphi rangifer tarandus

Hwæt, Hrodulf readnosa hrandeor—

Næfde þæt nieten unsciende næsðyrlas!

Glitenode and gladode godlice nosgrisele.

Ða hofberendas mid huscwordum hine gehefigodon;

Nolden þa geneatas Hrodulf næftig

To gomene hraniscum geador ætsomne.

Þa in Cristesmæsseæfne stormigum clommum,

Halga Claus þæt gemunde to him maðelode:

“Neahfreond nihteage nosubeorhtende!

Min hroden hrædwæn gelæd ðu, Hrodulf!”

Ða gelufodon hira laddeor þa lyftflogan—

Wæs glædnes and gliwdream; hornede sum gegieddode

“Hwæt, Hrodulf readnosa hrandeor,

Brad springð þin blæd: breme eart þu!”

This is the rendering into Modern English given in the original source:

Here begins the deeds of Rudolph, Tundra-Wanderer

Lo, Hrodulf the red-nosed reindeer—

That beast didn’t have unshiny nostrils!

The goodly nose-cartilage glittered and glowed.

The hoof-bearers taunted him with proud words;

The comrades wouldn’t allow wretched Hrodulf

To join the reindeer games.

Then, on Christmas Eve bound in storms

Santa Claus remembered that, spoke formally to him:

“Dear night-sighted friend, nose-bright one!

You, Hrodulf, shall lead my adorned rapid-wagon!”

Then the sky-flyers praised their lead-deer—

There was gladness and music; one of the horned ones sang

“Lo, Hrodulf the red-nosed reindeer,

Your fame spreads broadly, you are renowned!”

Of course, there is no Old English text that formed the basis of the Rudolph legend. This is a parody written by the American Philip Chapman-Bell in 1996 (“Hrodulf Harndeor: An Old English Poem by Philip Chapman-Bell”). You can see the original here in an archived version of his old website.

The heroic epic poem Beowulf is the most well-known work of Old English literature, studied throughout the English-speaking world. As the poem above demonstrates, Old English is nearly indecipherable for today’s English speakers who have not studied it. Given that even Shakespeare’s work from four centuries ago causes problems for today’s English speakers, it shouldn’t be a surprise that Old English spoken a millennium ago is practical a foreign language. This was exacerbated by the Norman conquest of England by William the Conqueror in 1066, which led to a period of rule by speakers of Norman (a language very close to French) and French itself. It was only in the 15th century that English started appearing in official documents again instead of French.

The first line of Beowulf is probably the most well-known line in all of Old English, familiar to generations of students.

Hwæt. We Gar-Dena in gear-dagum, þeod-cyninga, þrym gefrunon, hu ða æþelingas ellen fremedon.

Lo! We have heard of the glory of the kings of the people of the Spear-Danes in days of yore—how those princes did valorous deeds! (translation by John R. Clark Hall)

Old English hwæt means ‘what’ and is indeed the source of the modern word. Traditionally, the hwæt in the opening line of Beowulf was interpreted as an interjection to grab the attention of listeners (as Beowulf was originally a work of oral poetry), so besides “Lo!” it was also rendered as “Hear me!”, “Listen!”, etc. The 2000 translation by Irish Nobel laureate in literature Seamus Heaney uses “So!”. This use of hwæt is so iconic that it appears twice in the parody above.

Recently, however, Cambridge University’s George Walkden published a paper claiming that hwæt in Old English was not a standalone interjection but acted to introduce an exclamative clause (“The status of hwæt in Old English“, 2011). If this conclusion is true, then we have been mistranslating the opening line of Beowulf all this time. Instead of “Lo! We have heard”, it should be “How we have heard”. Also in the parody above, instead of “Lo, Hrodulf the red-nosed reindeer—That beast didn’t have unshiny nostrils!”, it should be something like “Hrodulf the red-nosed reindeer—How that beast didn’t have unshiny nostrils!”, although the double negation of Næfde ‘didn’t have’ and unsciende ‘unshiny’ makes such a rendering awkward.

Old English poetry uses a lot of alliteration (repetition of the first consonant sound) and figurative circumlocutions. The opening line of Beowulf has alliteration in Gar-Dena and gear-dagum, and in þeod-cyninga and þrym for example. Figurative circumlocutions, usually in the form of compounds, also features in other Germanic poetic traditions such as Old Norse poetry, and are called kennings after their name in Icelandic. Some examples of kennings in Old English poetry are banhus (ban ‘bone’ + hus ‘house’) for ‘human body’ or hronrad (hron ‘whale’ + rad ‘road’) for ‘sea’. The description of Danes as Gar-Dene (gar ‘spear’ + Dene ‘Danes’; Gar-Dena is the genitive form) is a similar descriptive device.

In the poem about Hrodulf (Rudolph), you also see these devices in action. There is alliteration in Hrodulf and hrandeor, and in Næfde, nieten, and næsðyrlas. There are circumlocutions such as hofberend ‘hoof-bearer’ for ‘reindeer’ and hrædwæn ‘rapid-wagon’ for ‘sleigh’. They expertly convey the feel of Old English poetry.

Rudolph is a Germanic name that can be reconstructed as *Hrōþiwulfaz in Proto-Germanic, a combination of *hrōþiz ‘fame’ and *wulfaz ‘wolf’. In Old English, this became Hrōþwulf/Hrōðwulf or Hrōþulf/Hrōðulf, so it is slightly disappointing that the poem above renders it as Hrodulf. The name wasn’t used much in English, and was reimported as Rudolph due to the influence of forms such as German Rudolf, Dutch Roedolf, and the Latin form Rudolphus. Famous bearers of the name include Holy German Emperor Rudolf II (1552–1612) and Nazi German politician Rudolf Hess (Heß in German spelling, 1894–1987), and former New York City mayor Rudi Giuliani’s first name also stands for Rudolph.

The element corresponding to Proto-Germanic *wulfaz ‘wolf’ is quite popular in Germanic names, and it also appears in Beowulf, the title character of the epic poem. The precise etymology is unclear, but if the first element is Old English beo ‘bee’, then the name could mean ‘bee-wolf’, possibly a circumlocution for ‘bear’ (bears are known for their love of honey).

Rangifer tarandus, which appears in the introductory line in Latin, is also the scientific name for reindeer given by Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus. In the original poem, it is rendered as ‘Tundra-Wanderer’, but this seems to have little basis in the actual etymology. According to Swiss naturalist Conrad Gesner (1516–1565), reindeer were called rangifer or raingus in Renaissance Latin, and were called reen by the Lapps (i.e. the Saami, the indigenous people of northern Scandinavia). However, as the various words for reindeer in the Saami languages are puäʒʒ, boazu, boatsoj, båtsoj, bovtse, etc. (source), it seems more likely that he mistook the mediaeval Scandinavian word deriving from Old Norse hreinn ‘reindeer’ as a Saami word. Old Norse hreinn seems to be connected to the Proto-Indo-European root *ḱer- meaning ‘horn’ or ‘head’.

Meanwhile, tarandus came from the beast called τάρανδος tárandos in Ancient Greek, mentioned by Classical Greek writers such as Theophrastus and Aristotle. It is said to be the size of the ox and to be able to change its colour. This may come from the reindeer’s fur changing according to the season.

The name ‘reindeer’ in English has nothing to do with the English word ‘rein’. The Old Norse hreinn ‘reindeer’ mentioned above was also combined with Old Norse dýr ‘beast’ in the form hreindýri, which is responsible for the Modern Icelandic word for reindeer, hreindýr. Swedish also had a similar form rendjur, although it is not used today. English ‘reindeer’ seems to come from a similar mediaeval Scandinavian form. But it probably didn’t use hrandeor already in Old English, despite its use in the poem above.

Old English deor, like its Old Norse cognate dýr, referred to any beast, not just deer. So in the poem above, laddeor would more accurately be rendered as ‘lead-beast’ instead of ‘lead-deer’. As it passed through Middle English, ‘deer’ came to be restricted to the modern sense. The fact that ‘reindeer’ in English is a type of deer is therefore a coincidence. German Rentier and Dutch rendier, the words for ‘reindeer’ in these languages, also derive from mediaeval Scandinavian like their English counterpart, but German Tier and Dutch dier just mean ‘beast’, not ‘deer’ specifically.

As a bonus, here is the Rudolf story rendered in sijo (시조 時調), a popular traditional Korean poetic form:

루돌프 사슴 코는 빨갛게 빛이 나서

나머지 사슴들의 놀림거리 되었으나

산타의 썰매 이끈 후 명성 널리 떨치네

Nameoji saseumdeul-ui nollimgeori doeeosseuna

Santa-ui sseolmae ikkeun hu myeongseong neolli tteolchine

The deer Rudolph’s nose glowed red

And became the object of the other deer’s ridicule

But after leading Santa’s sleigh, his fame spreads far and wide

The original Korean version of this post can be found here, including renderings of the poems in Korean.